GUEST COMMENTARY

by Trivan Annakkarage

The Belt & Road Initiative (BRI) of China is a widely discussed topic today since its concept is unique to the discipline of global geo-politics. This is because the latter is the study of how one powerful nation-state applies a grand strategy (it may be argued) to gain control over most of the world’s population and its resources. Grand strategies implemented by current and former world super-powers (such as the United States of America, Soviet Union, British Empire, Dutch Empire etc.) focused on exerting their power of influence either on land or sea through political and military might. However, BRI envisioned by China focuses on spreading its influence on both land and sea through mutually benefiting economic collaborations with other nation-states. Thus, the political leadership of China proclaims BRI as a revival of the ancient Silk Route.

The Belt and Road Initiative is China’s grand strategy to make its mark on the global geopolitical stage (Clarke, 2017; Ploberger, 2016). Curran (2016) states that the magnitude of this project is even larger than Marshall Plan which was USA’s initiative to financially aid Western, Central, Northern and Southern European countries to rebuild their economies after WWII. However, Shen and Chan (2018) object to this argument because they believe it is too early to make such a comment.

From 1948 to 1951 the Marshall Plan donated US$13billion to war-torn nation-states which are now part of the collective defence agreement, NATO (Shen & Chan, 2018). The present value of the Marshal Plan is estimated above US$135billion (Steil & Rocca, 2018). Contrastingly, BRI is estimated to spend over US$900billion to fulfil the infrastructure gap in more than 68 developing countries (Bruce-Lockhart, 2017). Therefore, if China’s Belt and Road Initiative comes into full realization it will be seven times larger than USA’s Marshall Plan.

President Xi Jinping first announced China’s ambitious project of reincarnating the ancient silk road and maritime silk routes at the Nazarbayev University in Kazakhstan and at the People’s Representative Council of Indonesia in 2013 (Cai, 2017; Phillips, 2017). According to The State Council: The Peoples Republic of China (2018), this road and maritime silk route was officially termed ‘Belt & Road Initiative’, and part of its mission is determined to lend a hand to those developing economies that require capital investment to boost their exports and logistic facilities.

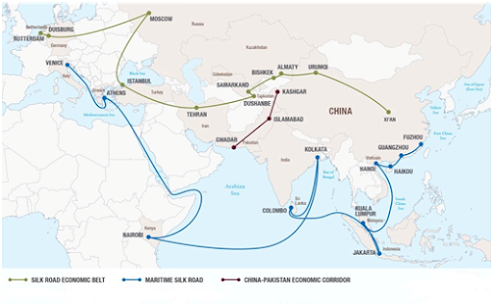

BRI thus focuses heavily on addressing the infrastructure gap in many developing nation-states which are members of this initiative (Cai, 2017). The governments of these nation-states have welcomed China and BRI with open arms (Xuequan, 2016). When this geopolitical grand strategy is fully realised, BRI will enable China to connect with the world through five routes. These include West & Central Europe through Central Asia and East Europe, West Asia through Central Asia, South Asia through South East Asia, Southern Europe through South China Sea, Indian Ocean, Red Sea, Suez Canal and Mediterranean Sea followed by South Pacific Ocean through South China Sea (HKTDC, 2018). The map below illustrates the above routes.

Through BRI China anticipates to fulfill four objectives. The first is to mitigate the over-dependency on existing sea lanes (Brady, 2017; Ploberger, 2016). This is because most of China’s trade flows through sea routes. As an ocean-based super-power, the United States has a strong presence in the Yellow, East China and South China Seas. This is a major concern for China because the security and uninterrupted journey of its shipping lines that pass through these waters depend on its relationship with USA. Since China is a potential rival for USA’s world dominance, the Government of China is wary of any strategic motive by its rival that can incapacitate China’s smooth flow of imports and exports (Harper, 2017). The second is to bridge the inconsistent economic disparity within China’s western and eastern populations.

Most of the wealthiest population resides in the metropolitan eastern coastline while the poorest live in the rural western interior. This growing disparity is considered a threat to China’s sovereignty because separatist movements in provinces such as Inner Mongolia, Tibet and Xinjiang-Uyghur blame the Government of China for the impoverishment of their people and justifies it as their cause for self-determination (Armstrong, 2012; Rao, Spoor, Ma & Shi, 2017; Reuters, 2015). The third is to provide employment opportunities to its growing working class (Shen & Chan, 2018) and the fourth is to exert its political, economic, cultural and technological influence on those 68 nation-states which are part of BRI (Albert, 2018).

It must be noted that China was well into implementing strategic solutions to curtail the above four issues through the Belt & Road Initiative before the COVID-19 pandemic disrupted all economic activity around the globe and it is rather poignant that the source of this virus was also from China. Since the beginning of 2020 BRI has experienced hostility from people round the world who criticize it as a sinister plan for China’s world dominance more so now than ever before. Taking this concern into account Beijing has decided to revamp BRI to meet present day demands.

COVID-19 highlighted the vitality of developing medical infrastructure facilities and not only focusing on commercial structures in order for its member nation-states to prosper economically. Beijing has therefore, captured this deficiency in BRI as an opportunity to re-invigorate the importance of their geopolitical super-mega project to give it a new meaning. To emphasize China’s concern in medical welfare, Beijing has introduced and incorporated the Health Silk Road concept into BRI in 2020. Furthermore, since the world is moving towards an internet based ‘working from home’ culture due to COVID-19, Beijing is focusing more on the Digital Silk Route in parallel.

The Health Silk Road is associated with providing medical supplies and medical teams from China (free-of-charge) to countries that are extremely vulnerable to COVID-19. According to Beijing this is done as a symbol of goodwill. The many countries benefitting from the Health Silk Road such as Italy, Iran and South Korea have embraced this initiative. However Beijing has not been clear on how the Health Silk Road would continue to operate if COVID-19 is fully eradicated. The Digital Silk Road on the other hand is a more ambitious project that was introduced in 2015(two years after BRI was introduced in 2013) by an official Chinese white paper. It deals with connecting BRI member states with China on a digital platform. The implementation of 5G through Huawei Technologies Group Co., Ltd. is just the beginning of Beijing’s vision to overpower USA’s dominance in the entire World Wide Web.

The Business Reporting Desk (2020) of the Belt & Road News site has stated several updates and changes Beijing wishes to incorporate in BRI so that this geopolitical endeavour better address present day requirements of developing and developed nation-states. Due to member states being adversely affected by the economic crisis caused as a result of COVID-19, China has announced it will cancel interest-free loans to countries in the African continent amounting to US$ 3.4 billion. These funds may be directed towards the Health Silk Road. However, Beijing has no intention to write-off commercial and concessional loans but to re-structure them on a case-by-case basis. This is a possible solution because BRI is largely bilateral than multilateral. However, this is a clear indication of China’s debt trap diplomacy. Nevertheless, it unreasonable to accuse China and its state run finance companies alone for such a devious strategy because Washington backed IMF and World Bank do not act any different.

Due to the logistical constraints imposed by COVID-19, there are discussions within the political elite in Beijing to re-think their current method of deploying Chinese boots, construction material and machinery in foreign infrastructure projects financed by Chinese loans. This system is known as EPC+F (Engineering, Procurement, Construction and Financing). The possible solution that Beijing might introduce is to contract public/private companies in those host countries to partner with BRI projects.This may be owing to BRI being criticized for limiting direct employment of local labour and expertise of the host nation. Therefore, this will provide opportunities for either public or private firms of the host nation to benefit thus providing a level playing field and countering various other accusations regarding the EPC+F model which is viewed as being only advantageous to China.

Buckley (2000), states that COVID-19 has further exacerbated the existent concerns regarding the necessity, feasibility and transparency of the infrastructure projects in member nation-states. Even before the pandemic there were cracks emerging between China and some host countries when executing projects. These were largely due to the debt burden related to asset seizures (such as the deep sea port in Hambantota, Sri Lanka; Khorgos Dry-Portin Kazakhstan; and Bar-Boljare Highway in Montenegro infamously referred to as the ‘highway to nowhere’). Learning from these experiences some countries have become sceptical of prospective BRI projects. Examples include Myanmar deciding to involve other international partners for its US$ 800 million Yangong City project and Sierra Leone cancelling the US$ 400 million worth Mamamah Airport project.

In addition to issues faced from BRI, China is being severely accused of intellectual property disputes and assertions of non-transparency in the disclosure of the origin and spread of the virus. During 2020 however, the latter has been highlighted more than the previous allegation. Hence Japan has extended loans to its companies operating in China to relocate back to Japan or to another country. This can be viewed as a strong diplomatic message to China.

In conclusion, the Belt and Road Initiative despite it being shrouded in ambiguity and lack of transparency will one day be fully realised even if it does not match up to the magnitude President Xi Jinping wishes it to be, due to his vision being overwhelmingly hampered by COVID-19. It is inevitable that China will one day defeat the existing American hegemony. Therefore Beijing will be the creator of a new world in the 21st century like what Washington did back in the 20th.The issue however is that although BRI would genuinely uplift the living the conditions of the people of its member nation-states, will the latter have to pay the heavy price of giving up their civic rights (such as free speech, public franchise etc.) and cultural identity which they currently enjoy, to the Communist Party of China? Therefore, let us hope this next super-power from the east would not turn out to be ruthless like a dragon but as compassionate as a panda.